Funny you should mention Rimbaud, of course. I like to think of him as a sort of emblem of what you might call, following Pushkin, the "lazy man". I like to say "the mope."

It's funny too, though, how mopes always seem to be the ones slamming open hidden doors. That monster Elvis, for example, was a classic lay-about. And have you ever read Truman Capote's New Yorker profile on Marlon Brando? The Duke, it seems, the torrent of American Acting, was really a fat, lazy bum at heart. And that's before he actually became a fat, lazy bum.

I love these guys, but I love them, mostly, for their mopiness. I aspire to Brando in Streetcar--cut, virile, ridiculously handsome--but really I feel more comfortable with Godfather Brando--fat, slow, a bit ugly. The one seems full of energy, but a little empty; the other, full of languor, and yet utterly powerful.

I mean, I always admired a guy like Neruda for his industriousness, but I didn't love him until I read his thoughts on wasting time:

"If poets answered public opinion polls truthfully, they would give the secret away: there is nothing as beautiful as wasting time."

But there's a difference, I think, between being lazy in life and being lazy in ART. For example, that bum Pushkin, you mention, throws grapes at us until we see that we've got to keep slapping ART, keep reminding it to pay attention and not lapse into the laziness of inherited forms.

Which is basically what Rimbaud says: "The invention of the unknown demands new forms". And, really, what poet's life better distills the essence of this quote than Rimbaud?

He wrote this famous line in 1871, at the age of sixteen, in the midst of a sequence of two brash and absurd letters that have come to be known as the Lettres du Voyant or, if you prefer, "The Seer Letters."

The first letter, to his teacher Georges Izambard, announced Rimbaud's intentions to become a poet, a seer, and it included a short poem, which begins with a choice Rimbaud line: "My sad heart slobbers at the poop."

Izambard blasted the letter. It was vicious, detestable he later said—the young poet seemed to want to screw himself up, as much as possible, physically, emotionally, and spiritually.

But Izambard missed the point. Yes, Rimbaud was screwing himself up, but he was serving an inviolable master: Poetry.

"Right now, I'm making myself as shitty as I can," he wrote. "Why? I want to be a poet, and I'm working at turning myself into a Seer. You won't understand any of this, and I'm almost incapable of explaining it to you. The idea is to reach the unknown by a derangement of all the senses. It involves enormous suffering, but one must be strong and be a born poet. And I've realized I am a poet. It's really not my fault."

This strikes me as one of the most pretentious, ridiculous letters ever written. And I love it. I love it for what it says about the connection between writing poetry and living poetry. The derangement of all the senses is one of Rimbaud's most celebrated phrases. With the support of this bold assertion, Rimbaud transformed the act of writing poetry into an act of living, a voyage into the wild unknown.

"The invention of the unknown demands new forms," Rimbaud wrote in the second of the Lettres du Voyant, sent to Izambard's friend, Paul Demeny, several months later. At this point, the young poet was certain: the new form was meant to be amorphous, as a man's life is, essentially, amorphous. And although Izambard and Demeny both dismissed the letters as utter inanity, practical jokes at best, utter filth at worst, Rimbaud was certainly not joking.

Within a few months he was carousing bohemian Paris, living on little else than absinthe, hashish, and the erotic adulation of Paul Verlaine, and writing his masterpiece, "A Season in Hell."

From poop to poetry—the evolution of Rimbaud was furious.

But still, I must admit, it is this early line that has always haunted me: my sad heart slobbers at the poop.

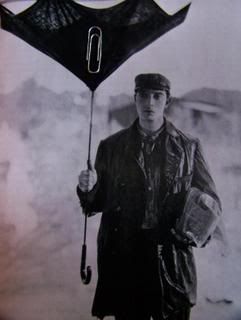

This line has occupied my thoughts for several years. It comes to me during the most opportune occasions. When, for example, alone and sitting on the toilet, I begin to imagine Rimbaud at sixteen, and I see the portraits of the young poet, the first taken in October, 1871, the second, more famous, taken two months later, in December.

The difference between the two pictures is astounding.

In the first picture Rimbaud, recently arrived in Paris, appears to be no more than a child, a puffy, mopey brat, eminently poised for naughtiness—the type of child who seems capable of writing an entire manifesto on poop.

In the second picture, Rimbaud has aged considerably; his face, chiseled, evocative—Jean Cocteau said, "He looks like an angel"—is the face of a poet, a man.

What possibly could have happened in the span of two short months to bring about this incredible transformation?

Sometimes I linger on the toilet, for up to ten, fifteen minutes, my chin positioned firmly on my fist, thinking about Arthur Rimbaud's life. I can see him, for example, standing on some non-descript corner in the Latin Quarter, kicking a stone, a seventeen year old absorbing the hitherto unfamiliar language of the world that was Paris in 1871: the dung-filled alleyways, the aroma of bodies and smoke, the muggy air. Then, in the evening, when the darkness collapsed upon the city, he would have strolled along the streets until he hit the small alley, the Rue Séguier, where a metal cot awaited him in a studio at number thirteen, the second of four, five, or six addresses in Paris, the filthy rooms where he conceived the lines that won him posthumous worldwide fame.

But eventually my thoughts always turn to his life after Paris, his years of wandering, and his death in Marseilles. The biographies tell us that in 1874, though possibly later—the life of Rimbaud has always remained splendidly ambiguous—he quit writing, irrevocably.

Rimbaud—the seer-poet—was nineteen years old.

He spent the next seventeen years wandering around Europe and Africa. This period of his life is sketchily documented, often vague, and mysterious. His letters, written during the time, reveal a sullen, mopey man. "I am bored all the time," he wrote to his family in 1888.

By the time he died, in 1891, in Marseille, after years of wandering, his poetry had resurfaced in France, but Rimbaud had vanished so completely that many people did not believe the news of his death: they assumed he was already dead. Rimbaud—the wanderer, the mope—was thirty-seven years old.

Rimbaud's life—the early, resounding poetry; the sudden, unreasonable renunciation of poetry; and the inscrutable years of wandering that follow—has fascinated and perplexed me for some time. And this is why I have chosen to evoke him now—as a resounding testament to the intrigue of mopey behavior. And yet, when I am on the toilet, thinking, and even now as I write, I am confounded by what seems to be the inscrutable enigma of Rimbaud.

After all, what is one to make of this enigmatic character?

How am I to evoke the unreasonable Rimbaud?

Was he a seer? Or a mope?

Whatever the case, it's obvious there was a lot of Not-Writing that led to Rimbaud's writing: a lot of getting ready. Does it really matter what you do to get ready, though? Probably. I tend to think boring lives inspire boring writing. But then, of course, there's the Emily Dickinson factor. She basically sat around her place a lot, but she sure wrote a lot of kick-ass poems.

Did she even do drugs? I don't think so.

I suppose the connection between Not-Writing and writing might be too subjective to qualify at all. We all get ready in different ways, of course. Writing, though, the act of sitting down and doing the work--that's easier to define. You sit down, do it. I know you might find that attitude naive, a bit ridiculous, but that's how I've always gone about it.

I live, get drunk, wake up hung-over, and sit down and write. If I don't make this commitment to sitting down, each day, I'll never write. When I'm Not-Writing I don't think about it. I try, instead, to give my attention to what really matters, at least to me: my wife, my friends, my family, food. Funny thing though, this attention, this look away from writing, is me writing too.

Basically, I'm always preparing, but not always thinking about the preparation. That puts an awful lot of stress on your life. Deliberately going out to derange your senses in the service of writing? That's childish. I'll just go out and derange my senses.

Hemingway was a dick-head, for sure, and part of this might have been his need to live experiences for writing. That strikes me as extremely artificial and very bullshit.

Perhaps that's why I prefer the mopes, the ones who love wasting time, which really has nothing and everything to do with the time they spent writing--which, of course, was not wasted time at all...